Using Large Language Models to Simulate and Predict Human Decision-Making

We explore how large language models can be used to predict human decisions in language-based persuasion games, comparing direct prompting, LLM-based data generation, and hybrid methods that mix synthetic and human data.

Can large language models (LLMs) help us predict what humans will do in strategic, language-based interactions, such as persuasion games, bargaining, or recommendation settings? In this blogpost, we explore several concrete ways to use LLMs to predict human decisions in a particular language-based economic environment.

Our main messages are simple. First, you can indeed use LLMs to predict human decisions in this kind of game. Second, in our experiments, it is often more effective to use LLMs as data generators for small predictive models than to rely on them as direct classifiers. Third, even when human data exists, incorporating LLM-generated data into the prediction process can improve performance and, with the right method, maintain reasonable calibration. The blogpost is based on our long paper

Why predict human decisions with LLMs?

Many systems need to anticipate how humans will react: will users trust a recommendation or ignore it, accept an offer or walk away, follow a suggestion or resist it? Accurate prediction of human decisions can help us design mechanisms that are more efficient or more fair, run virtual experiments without recruiting thousands of participants, and stress-test systems before deployment by simulating how people might respond in different conditions.

From a behavioral-economics perspective, forecasting decisions is challenging because people care not only about monetary payoffs but also about fairness, reference points, and social preferences.

However, two practical constraints often arise. First, when designing a new system or game, we may have no human interaction data at all. Running a large-scale behavioral experiment is expensive and time-consuming. Second, even once we have run an experiment, the amount of human data is typically limited: a few hundred or a few thousand decisions, spread across many conditions and histories. In that regime, every additional bit of signal is valuable, and we want to use the available data as efficiently as possible.

Recent progress in LLMs, from GPT-3 and GPT-4 to PaLM 2, Gemini, and Qwen-2, has shown that scaling up language models can yield strong performance on a broad range of NLP and reasoning benchmarks.

LLMs offer a natural way to supplement the sparse information we typically have in behavioral datasets. They have been trained on massive text corpora, can be prompted to play the role of agents in games, and can generate synthetic data that sometimes resembles human behavior. The central question we tackle is therefore: given a specific decision-prediction problem, how should we best combine human data and LLMs to predict behavior, and what trade-offs arise between accuracy, calibration, and computational cost in that particular setting?

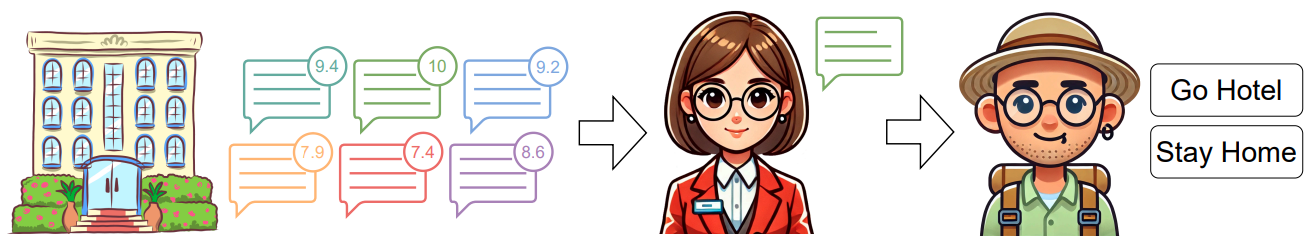

Our playground: language-based persuasion games

We study these questions in a repeated persuasion game about hotel bookings, firstly presented by

Persuasion games of this sort connect to a rich literature in economics on communication, reputation, and information design.

This game is repeated across several rounds with the same expert–DM pair. Over time, the DM can learn about the expert’s behavior: if the expert tends to recommend good hotels, trust should increase; if the expert repeatedly highlights bad hotels, trust should erode. In the human experiments underlying this blogpost, participants played against several different expert strategies, such as always sending the highest-scoring review, always being honest, or adapting to the DM’s past decisions and outcomes. The resulting dataset consists of many human decisions across a variety of histories and expert behaviors.

Our prediction task is: given the interaction history so far and the current review shown by the expert, predict whether the human will choose “Go Hotel” or “Stay Home”. All of the numbers we report in this blogpost are measured on this specific prediction task, using the particular data collection protocol and model configurations described below.

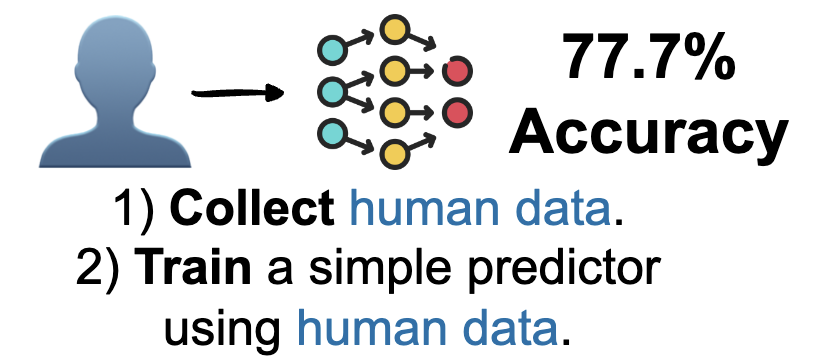

Baseline: learning directly from human data

We begin with the most straightforward approach: collect human data for the hotel game and train a small predictive model directly on these human decisions. To do this, we represent each decision with a set of features that encode both the current review and the interaction history. Features include information about the review itself (such as sentiment and score) and about the past rounds (such as how often the expert has previously “lied”, previous choices and payoffs, and trust-related patterns). A small model—such as an LSTM over the history , a tabular method over handcrafted features or teaxtual-tabular model over the messages and the features — is trained to predict the DM’s action.

For the purposes of this blogpost, we focus on a clean subset of the data collected by

In this configuration, a classifier trained only on human data achieves 77.7% accuracy on held-out players. This serves as our main reference point for the rest of the blogpost: it shows how well a small, relatively inexpensive predictor can do in this specific environment when trained on the available human data.

We also train a language-only baseline that sees only the current review, without any history features. This model achieves 76.5% accuracy, just 1.2 percentage points below the full human baseline. At first glance, this might suggest that using history brings only a small marginal gain. However, a more detailed analysis in

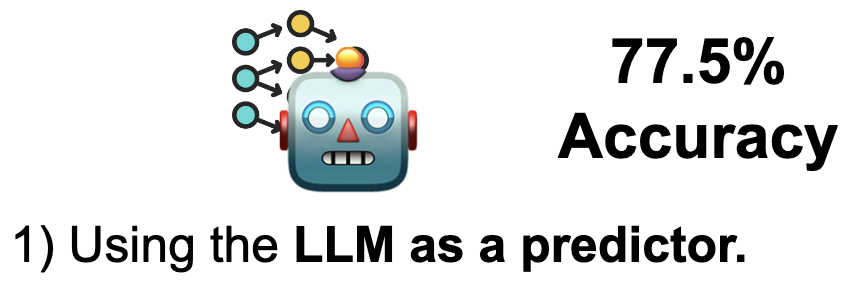

LLM as a classifier

The most obvious way to use an LLM is to treat it as a direct classifier. For each decision in the dataset, we construct a natural-language prompt that describes the game, the full interaction history so far, and the current review. We then ask the LLM a question such as “Will the human decide to go to the hotel or stay home in this situation?” and map its answer to a class label.

This naive approach has clear advantages. It requires no additional training or fine-tuning, and from a software engineering perspective it is easy to deploy: one only needs to maintain the prompt and call the LLM at inference time. It is especially attractive when we have a limited number of predictions to make or when we want to quickly prototype on a new decision problem. Treating LLMs as zero-shot or few-shot classifiers in this way echoes a broader trend in NLP.

At the same time, treating the LLM as a classifier has significant drawbacks. Each prediction involves running a large, multi-billion-parameter model, which makes inference expensive in terms of both compute and latency. When we need to make many predictions or operate in a real-time system, this cost can quickly become prohibitive. Furthermore, the model behaves as a black box: it is harder to inspect or compress into a smaller predictor.

In our hotel game, the naive LLM-as-classifier approach reaches 77.5% accuracy on the held-out human players. This is slightly better than the language-only baseline (76.5%) but slightly worse than the small human-trained model that uses history (77.7%). In other words, in this specific setting, using a large LLM directly as a classifier is competitive with, but does not clearly outperform, a carefully engineered small model trained on human data, while being much more expensive to run.

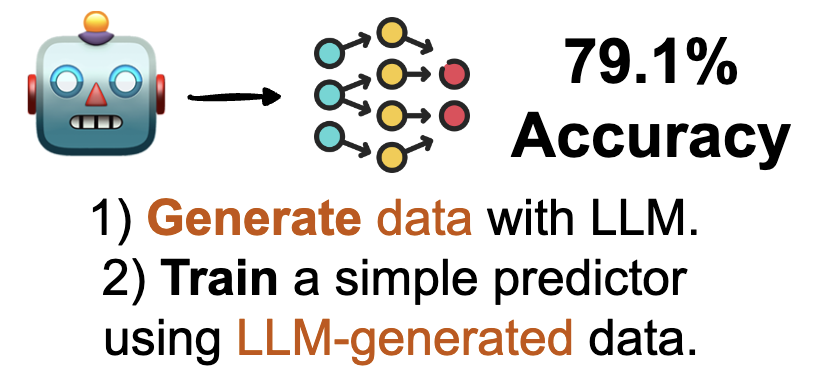

LLM as a data generator

Instead of using the LLM as a direct predictor, we can use it to generate synthetic data and then train a small classifier on that data. Concretely, we treat the LLM as a synthetic human player in the hotel game. We prompt it as if it were a DM, allow it to play repeated games against the expert strategies, and record its decisions. Repeating this process many times yields a large synthetic dataset of “LLM players”, each with full interaction histories.

Once we have the synthetic dataset, we train a small model (such as an LSTM or a tabular method) on LLM-generated data only, using the same feature representation we used for human decisions. We then evaluate the resulting small predictor on the real human test players. This experiment addresses a “no human data” scenario in a controlled way: in our implementation, we still have human data for evaluation, but the model used at inference time has never seen any human decisions during training, only LLM behavior.

In our hotel game, we find that as we increase the number of synthetic players, the performance of the small classifier improves. With 512 LLM-generated players, the small model already exceeds 78% accuracy. When we increase the synthetic sample to 4,096 LLM-generated players, the small model reaches 79.1% accuracy on the human test set. This is higher than the 77.7% human-only baseline from the same environment, despite the fact that no human decisions were used for training the predictor.

These numbers are specific to the hotel persuasion game and our particular experimental protocol, but they illustrate an important qualitative point: in this setting, LLM-generated data can be more informative for prediction than the limited amount of human data that we can feasibly collect. At the same time, the predictor we deploy is a compact model, so inference remains cheap and low-latency.

Incorporating human data into the process

So far, we considered two extremes within our hotel game: a small model trained only on human data, and a small model trained only on LLM-generated data. In realistic applications, we often have some human data, but not a lot. The natural question is how to best combine this human data with LLMs: should we fine-tune the LLM, train a small model on a mixture of human and synthetic data, or both?

In this section, we discuss three methods that incorporate human data into the process in different ways. All of the numbers in this section are again specific to our hotel persuasion game and to the exact splits and model configurations described above.

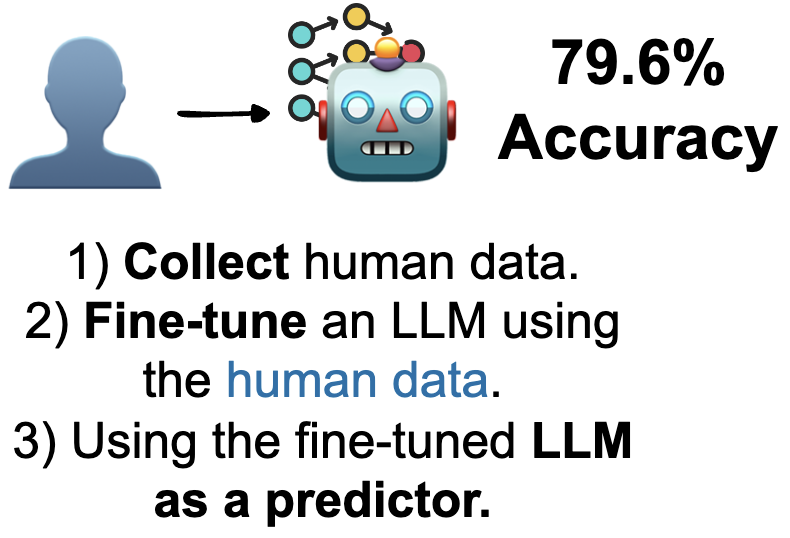

Fine-tune the LLM and use it as a classifier

The first method fine-tunes the LLM itself on human data and then continues to use it as a direct classifier. We start from a pre-trained LLM, fine-tune it on the training portion of the human hotel dataset (110 players), and then use the fine-tuned model to predict decisions for the held-out human players, given history and current review.

In this configuration, the fine-tuned LLM achieves 79.6% accuracy on the human test set. In our experiments, this improves both over the human-only baseline (77.7%) and over the small model trained solely on LLM-generated data (79.1%). The price we pay is that inference still requires running the full LLM, so the method inherits the computational cost and latency of the naive LLM-as-classifier approach.

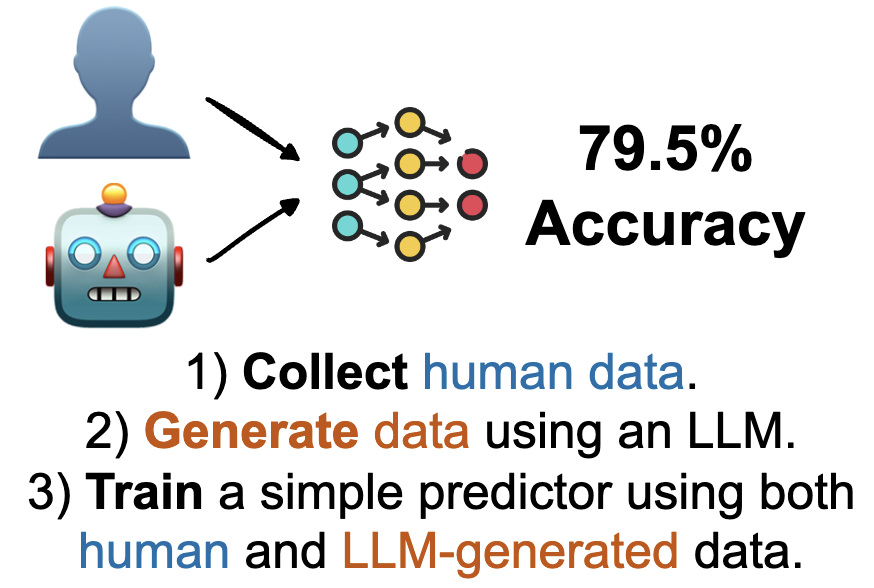

Train a small model on Human + LLM data

The second method remains committed to using a small classifier at inference time, but trains it on a mixture of human and synthetic data. We again keep the 110 human training players, generate a large number of LLM players using the base (non-fine-tuned) LLM, and pool the resulting decisions. We then train a small model on the union of human and LLM-generated data, using the same features as before.

In our hotel game, this Human + LLM data approach yields 79.5% accuracy on the test humans, almost identical to the 79.6% achieved by the fine-tuned LLM classifier. The advantage is that at inference time we only use a compact model, so predictions are much cheaper to compute. Importantly, this accuracy figure again refers specifically to the hotel persuasion game; our broader lesson is that, at least in this environment, combining limited human data with synthetic LLM data can give a small model performance comparable to that of a fine-tuned LLM classifier.

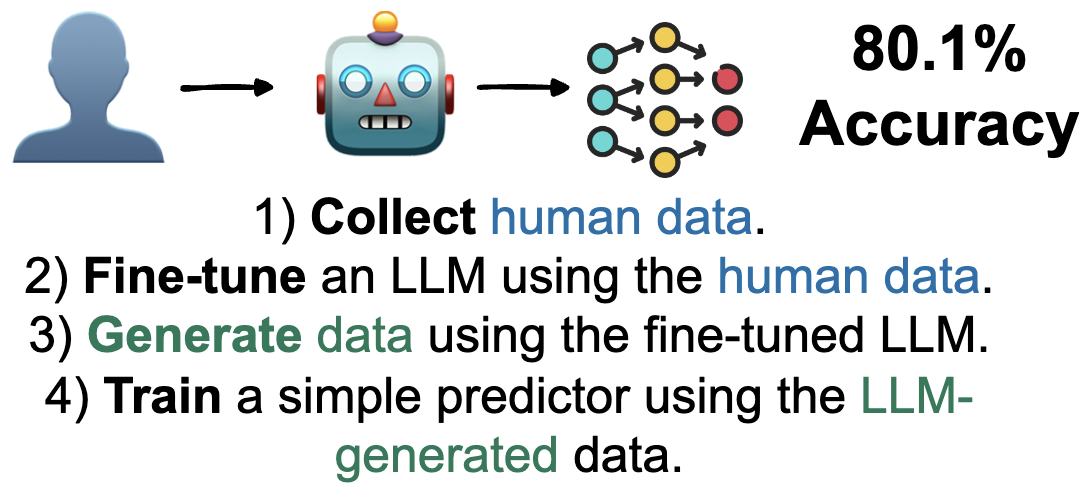

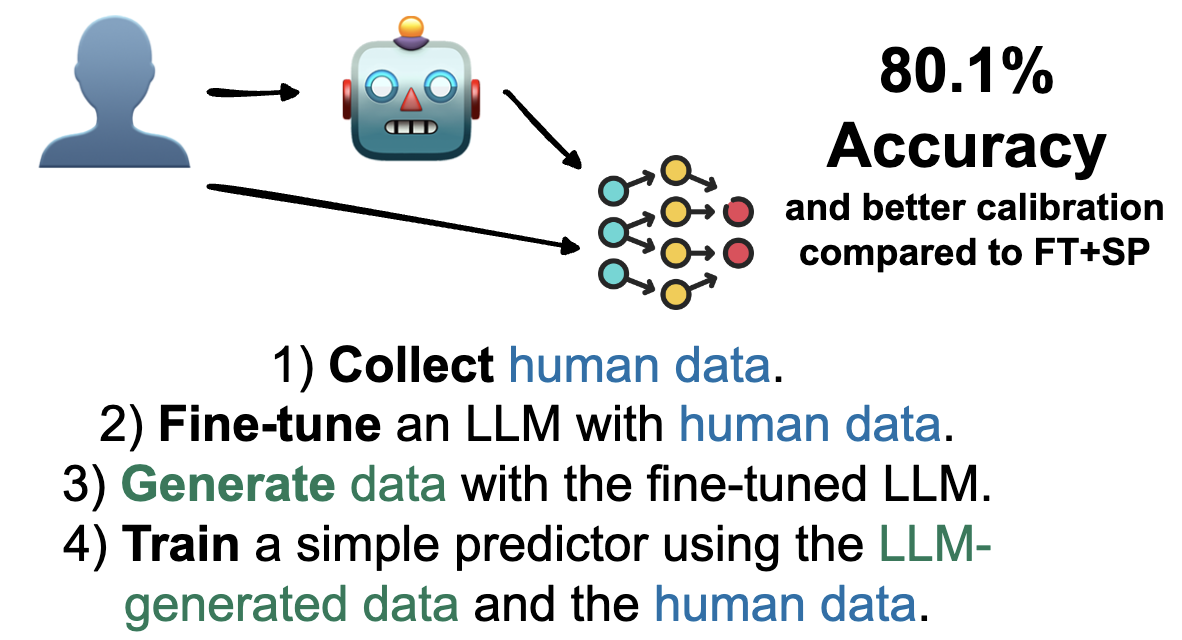

Fine-tune the LLM and use it as a data generator

The third method combines fine-tuning and data generation. We first fine-tune the LLM on the human hotel data, and then use this fine-tuned model, rather than the base LLM, as the generator of synthetic players. The small classifier is trained on these fine-tuned LLM-generated players only, and then evaluated on human test players.

In our experiments on the hotel game, this “fine-tuned generator” approach attains the highest accuracy among all methods we considered: 80.1% accuracy on held-out human players. As before, this number is specific to our data and configuration, but it shows that fine-tuning the LLM and then using it to generate synthetic players can be very powerful in this particular setting. The final model used at inference time is still a small classifier, so we benefit from both strong performance and inexpensive prediction.

Accuracy vs. calibration: the hidden cost of synthetic data

Accuracy is not the only quantity that matters when predicting human decisions. Our models also produce probability scores, such as “80% chance of Go Hotel”. We would like these probabilities to be well calibrated, meaning that among all decisions for which the model predicts an 80% probability, roughly 80% of the outcomes should indeed be Go Hotel. Poorly calibrated probabilities can lead to overconfident or misleading decisions downstream, even when accuracy is relatively high.

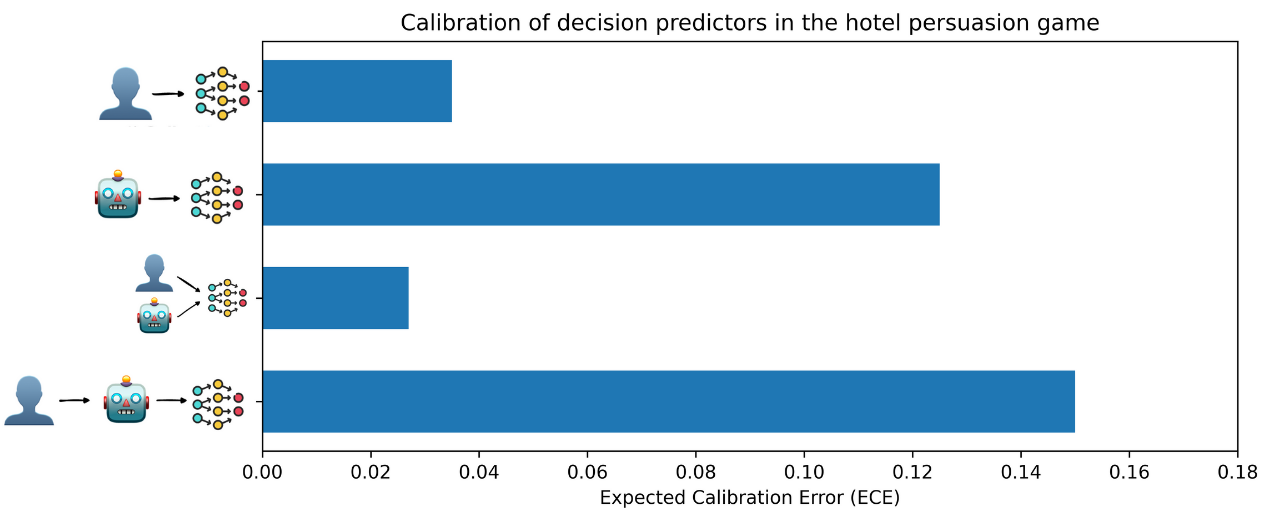

We measure calibration using Expected Calibration Error (ECE), where smaller values indicate better calibration. In our hotel game, we obtain the following ECE values:

These numbers again refer only to our hotel persuasion game. Within this environment, several patterns emerge. The human-only small model is well calibrated, with an ECE of 0.04. Methods that rely heavily on synthetic data alone, whether from the base LLM or from a fine-tuned version, show much worse calibration, with ECE around 0.13. Interestingly, training a small model on a combination of human data and base LLM-generated data yields both strong accuracy and very good calibration (ECE ≈ 0.03).

The fine-tuned generator method, which achieves the highest accuracy in our experiments (80.1%), has ECE ≈ 0.15. In the hotel game, this means that increasing accuracy by about 0.5 percentage points beyond the fine-tuned LLM classifier comes at the cost of significantly degraded calibration. Whether this trade-off is acceptable depends on the intended use: some applications care only about the top label, while others critically depend on well-calibrated probabilities.

DUAL: double use of human data for augmented learning

To mitigate the calibration problem while preserving high accuracy in our hotel game, we propose DUAL, which stands for “Double Use of human data for Augmented Learning”. The core idea is to use the same human dataset twice in the pipeline: once to fine-tune the LLM that generates synthetic data, and once to train the final small classifier on a mixture of human and synthetic data.

The procedure is as follows. First, we fine-tune the LLM on the human hotel data, just as in the “fine-tuned LLM” and “fine-tuned generator” setups. Second, we use this fine-tuned LLM to generate synthetic players for the hotel game. Third, we train a small classifier on the combination of human decisions and fine-tuned LLM-generated decisions.

In our hotel persuasion game, DUAL achieves the same accuracy as the fine-tuned generator method—80.1% on held-out human players—but with markedly better calibration. Its ECE is around 0.08, which is not as low as the 0.03 achieved by the Human + base LLM data method, but substantially better than the 0.15 observed for methods that rely solely on synthetic data from a fine-tuned generator. Thus, in this specific environment, DUAL balances high accuracy with improved calibration by reusing the human data at two stages of the pipeline.

Takeaways and open questions

All of the quantitative results in this blogpost are specific to a particular decision-prediction problem: a repeated hotel persuasion game with fixed expert strategies, a certain human experiment design, and specific model choices. Different tasks and setups could behave quite differently. Within this case study, however, several qualitative takeaways emerge.

First, LLMs can indeed help predict human decisions. In our hotel game, even when the small classifier is trained only on LLM-generated players and never sees any human decisions during training, it reaches 79.1% accuracy on held-out humans, outperforming the human-only baseline. This suggests that, in at least some environments, synthetic data from LLMs can meaningfully supplement or even partially substitute for small human datasets.

Second, using LLMs as data generators for small models can be more attractive than using them as direct classifiers, at least in the setting we studied. The naive LLM-as-classifier approach is simple but expensive and does not clearly beat a carefully designed small model trained on human data. In contrast, LLM-as-generator approaches allow us to train compact predictors that are cheap to run while still reaching strong accuracy. In our hotel game, the best-performing method (80.1% accuracy) is a small classifier trained on data from a fine-tuned LLM generator.

Third, even after human data has been collected, incorporating LLMs into the prediction pipeline is still beneficial. Mixed methods that combine human decisions with LLM-generated decisions often improve both accuracy and calibration relative to human-only models. In our experiments, the DUAL approach—fine-tuning the LLM, generating synthetic players, and then training a small classifier on both human and synthetic data—achieves the best accuracy and significantly better calibration than methods that rely solely on fine-tuned synthetic data.

A conceptual lesson is that history matters. In the hotel game, models that capture how humans use interaction history—how trust in the expert evolves, how past outcomes influence future choices—produce synthetic data that is more useful for prediction than models that only match the sentiment or surface form of individual reviews. Predicting human decisions in strategic environments is not just sentiment analysis; it requires representing and reasoning about how incentives, trust, and learning interact over time.

Many open questions remain. How robust are these findings to other types of games or tasks, such as bargaining, negotiation, or recommendation dialogues?

We hope this case study illustrates that LLMs are not only tools for generating text or acting as autonomous agents. In suitable settings, they can also serve as powerful data generators that, when combined with human data and calibrated carefully, help us better understand and predict human decision-making in language-based environments.

PLACEHOLDER FOR ACADEMIC ATTRIBUTION

Or use the BibTex citation:

PLACEHOLDER FOR BIBTEX