Towards LLM-based Experimental Economics

This blog post explores how Large Language Models (LLMs) can revolutionize experimental economics by simulating human behavior in foundational economic scenarios, while steering AI from zero-sum games to general non-cooperative games and agents towards strategic entities in a multi-agent environment. Traditional approaches in economics are limited by the costs and complexities of human-based experiments, and replacing humans with LLMs enables large-scale simulations, allowing researchers to examine a variety of economic mechanisms.

Introduction

There are three basic approaches to scientific studies: empirical, which relies on collecting observational data from real-world settings without intervention; experimental, which involves manipulating variables in a controlled environment to examine cause-effect relationships; and theoretical, which focuses on developing models and frameworks to explain or predict phenomena without direct data collection or experiments. In the context of economics, economic theory aims to make predictions using stylized models and solution concepts, mainly ones derived through equilibrium analysis. Experiments can be applied in the field or the lab, and the field of behavioral economics uses lab experiments to contrast theory prediction as well as to test alternative models, e.g. the introduction of prospect theory

Game Theory and AI

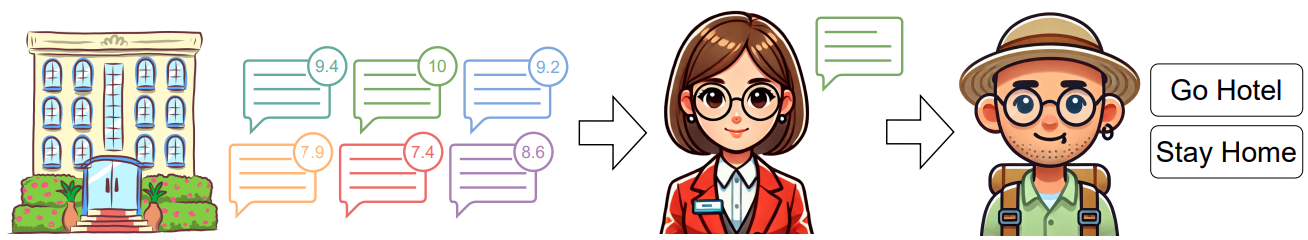

Of particular interest is the field of game theory. This field has originated in close time and place proximity to AI. Indeed, some of the early Turing Award recipients in AI were roommates in the same graduate school as some of the early Nobel prize recipients in economics associated with game theory. Unlike former economic models, game theoretic models are very mechanistic and focus on detailed strategic aspects of well-specified interactions rather than focus on price equilibrium in large markets, making it ideal for synergy with work focusing on multi-agent systems in AI. Indeed, the field of RL, for example, is shared among these areas

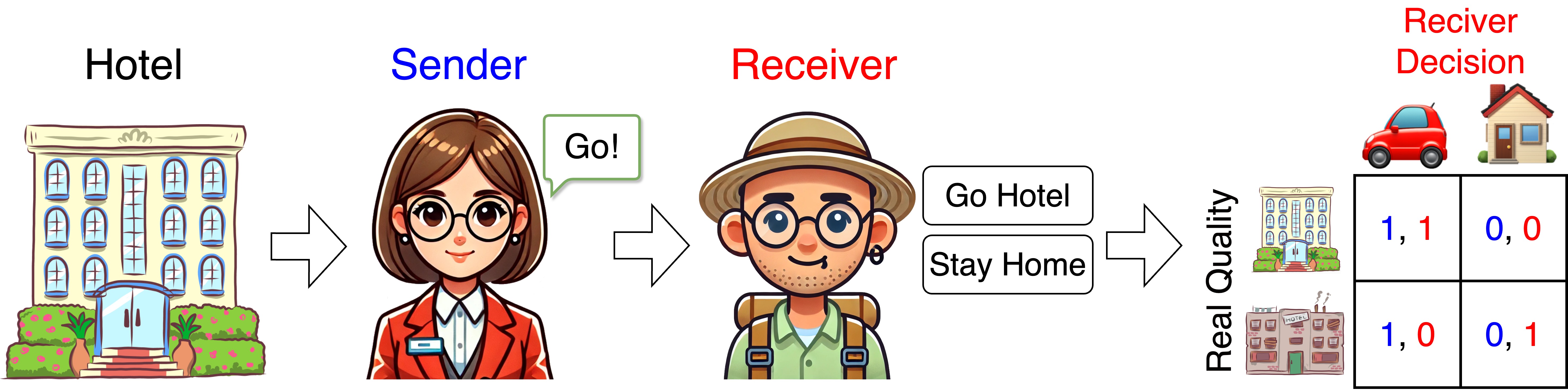

Modern work in economics, however, took very different directions from work in AI, mainly due to its focus on general non-cooperative games rather than zero-sum games. Indeed, when a seller tries to persuade a buyer to buy a product, there may be outcomes that are better for the seller and outcomes that are better for the buyer, but both have some joint incentive not to decline a mutually beneficial outcome.

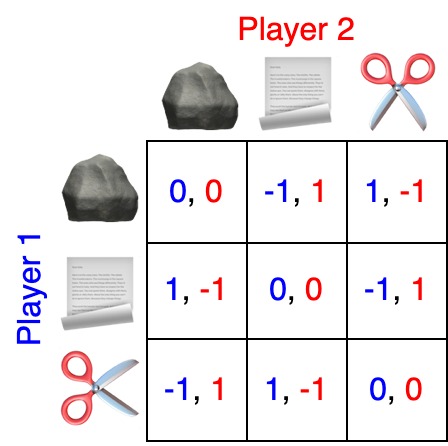

A classic example of such a non-cooperative game is the persuasion game, involving two players: the sender and the receiver. The sender holds information about the state of the world that is only visible to them and can send a stylized message—a predefined, simple message—to the receiver. The receiver uses this message, along with their knowledge of the prior distribution for the state of the world, to make a decision. The combination of the actual state of the world and the receiver’s decision determines the payoff for both players. An instance of this game was presented by

In almost no case are economic games zero-sum games. This led to notions of equilibrium (fixpoint) solutions as predictions for behavior in economic interactions on the theory side.

Challenges and Opportunities with ML and LLMs

As can be understood from the above, AI took an agent perspective dealing with computational agents in classes of games, highly connected to optimization, which are in most cases vastly different from fundamental non-cooperative games discussed in the economics literature. On the other hand, as the latter are not reduced to optimization problems the predicted behavior is non-trivial for analysis and/or for behavioral study. Indeed, both game theoretic analysis and its experimental study are highly limited, despite their shining successes; the game theoretic analysis is limited both by the fact analysis might become easily intractable and moreover by lack of “right solution”; the experimental study is limited due to very high cost and limitations of controlled experiments with human subjects. In recent years, computer scientists have looked closely at algorithmic aspects of game theory under the title Algorithmic Game Theory

Both economic theory and behavioral economics lab experiments possess two desired properties: simplicity and controlability. In other words, they allow us to focus on studying well-defined tractable frameworks while isolating unobserved or hidden effects. Simplicity allows for easy analysis (e.g., computing an equilibrium, either as a solution or while refuting its fit), while controllability allows to overcome dealing with sophisticated causal effects of unseen variables. Indeed, the latter is one of the big challenges empirical studies need to address. The challenge, however, is that the above setups (a) might be too remote from real-world natural settings and (b) will not allow to experiment with a wide variety of settings when considering alternative economic mechanisms. These are exactly the aspects that the current ML revolution allows to handle.

To explain (a) above, consider the following. Celebrated sender-receiver / information design models in economics (persuasion, negotiation, bargaining) simply ignore the use of natural language while considering only stylized messaging! We believe a good compromise is introducing a desired property, which we term adequacy, and can be addressed by emergent ML technology. The adequacy requirement refers not only to incorporating natural acts such as natural language but also makes it possible to consider more elaborated versions of simplified settings such as ones taking into account repeated interactions. This may make the situation infeasible to analyze if we would like to achieve a “closed form formulas” predictions of behavior. One important example is the use of natural language, which has no natural fit with standard mathematical economic theory models. However, ML can come to the rescue. In this context, behavior in language-based non-cooperative games (where natural language is used) will be treated as an ML problem – given the training data of some users predict behavior of other users

In summary, ML can attack (a) through obtaining adequacy and predictability, widely extending experimental economics to deal with language-based non-cooperative games. However, this is still limited, as we do not handle (b), beacause obtaining training data for particular game configurations is highly costly. The missing ingredient is scalability: how can we test for behavior with a huge number of parametrizations?

Recent research has explored how closely LLMs can approximate human behavior. Prior studies have highlighted the capacity of LLMs to perform on creativity assessments

These growing lines of research inspire to ask whether the ability of LLMs to behave like humans implies they can function as training data generators for human choice prediction

A Rigorous Approach to LLM-Based Experimental Economics

How can we approach the above in a rigorous manner? Basically, we need to follow five steps:

- Create a parametrization of a domain of non-cooperative economic games and formalize means to measure economic outcomes in such games.

- Generate data sets of the variety of LLM-based interactions in the corresponding games under the variety of the parametrization.

- For some parameterizations, perform the more classical behavioral economics lab study, where, e.g., some of (or even all) the participants are humans.

- Compare the ability to predict human behavior using LLM data with the ability to predict human behavior based on human data.

- Check and compare the economic outcomes for the variety of parameterizations of the LLM players, potentially selecting favorable ones and validating them with additional experiments with human subjects.

An illustration of the above is provided in

The intersection of economics and LLMs holds significant potential for advancing both fields. While current LLM Agents are designed to perform tasks aligned with operator objectives (see

In conclusion, the integration of economics and LLMs offers an opportunity to significantly advance both fields. Thanks to the scalability and advanced capabilities of LLMs, we can overcome long-standing limitations in experimental economics, leading to unprecedented progress in economic research—both in predicting human behavior and designing optimal economic mechanisms. Integrating LLMs into economic research will also pave the way for developing sophisticated AI agents capable of operating in non-cooperative, multi-agent environments, which constitute the majority of human interactions in the world we live in.

PLACEHOLDER FOR ACADEMIC ATTRIBUTION

Or use the BibTex citation:

PLACEHOLDER FOR BIBTEX